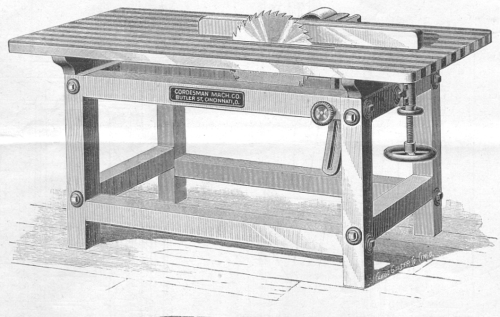

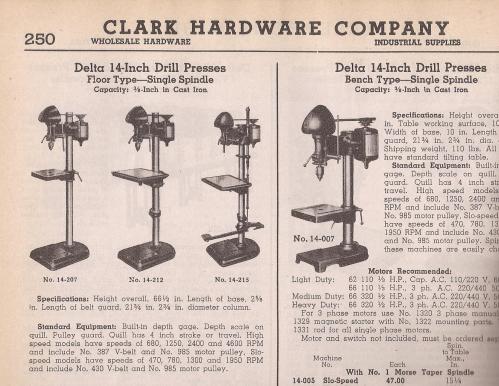

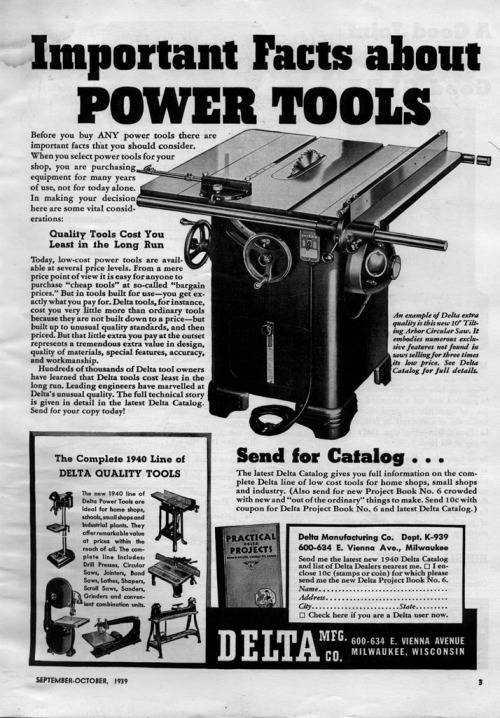

One of the challenges in creating a new piece of furniture from antique machinery — in this case, a dining table/kitchen island from a table saw — is marrying inspiration with the limitations of working with an existing utilitarian product. Certain aspects can be altered, others can be removed, but ultimately the character and history of the item need to be respected and highlighted.

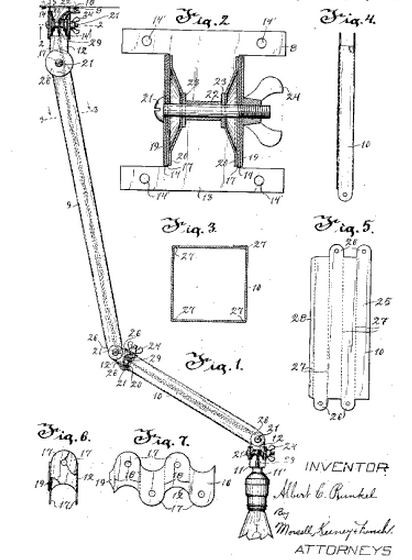

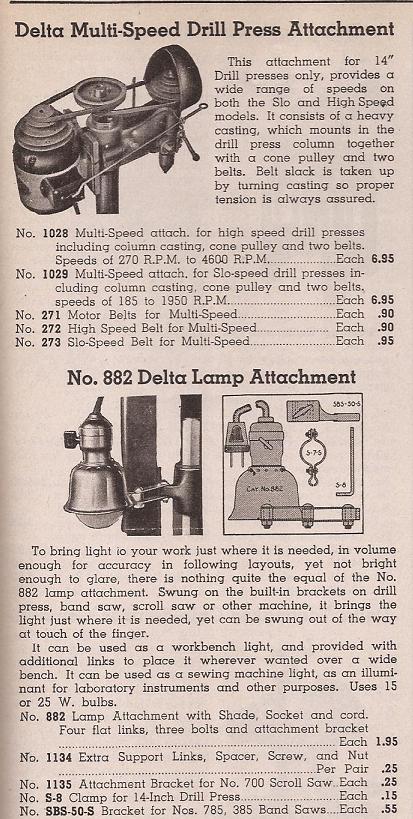

When acquired, the early-20th-century table saw that became the platform from which to create a new, home-friendly furniture piece had immediate appeal. Not only was its hefty frame solid and well constructed, it contained all of its original details, including iron hardware and a start/stop switch. The hand-painted number adorning it, “48,” suggested that it was one of many machines operating within its native wood-mill habitat.

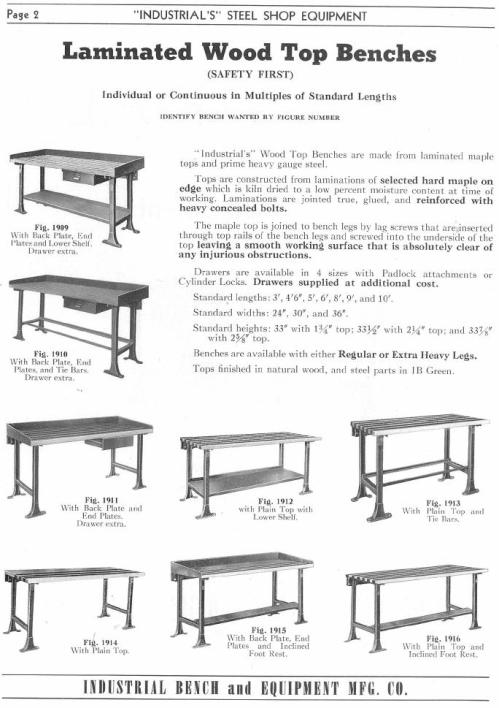

After we removed the saw-blade mechanism and belt, then unbolted the hardwood top, the opportunity arose to utilize some of these residual parts to create a lower shelf. Sections of usable material were cut and carefully pieced together to produce a sturdy storage space, perfect for pots and pans. A thorough cleaning of the original base revealed rich grain tones that, once clear-coated, intensified in color. A salvaged workbench butcher block proved aesthetically complementary while also adding a much larger surface area for additional seating. The finished table not only serves as a practical decor item but also becomes a gathering place conducive to conversation and shared experiences.

Join us on

Join us on